MAKOLA QUEENS

Civic spaces and identities are not restricted to physical structures or buildings, but can exist in a variety of forms, including objects, time and measurability. The civic-ness of a space or identity can be assessed at the scale of the human experience and the various interactions that occur within it. Makola market, a critical part of Accra’s economy, is the second largest informal market in the world. Trading within its boundaries, the market is home to a diverse array of vendors, selling everything from fresh produce to textiles, clothing and crafts. The government’s attempts to construct large scale infrastructure for the market are facing opposition from the local population, indicating that a top-down approach might not be the most effective strategy for the development of the space. Given this understanding, how can we design for a segment of the society that lives with the temporality of everyday life? How can we create a sense of ownership over space and provide agency to individuals who want to have an identity within the common collective?

Semester : Spring

Site : Accra, Ghana

Faculty : Gary Bates

Studio : Civic Futures

makola market

It is essential to the hypothesis that we design for stakeholders that face the brunt of the social hierarchy and support their needs in a way that allows them to feel empowered when they leave their homes. The aim is not to establish and heighten the stratification that exists today, but to offer opportunities for improving conditions for traders; and supplement that with developing organizational schemes that coordinate the provision, maintenance and use of the intervention. Our objective is to address the intricacies present in Accra by incorporating trust, impermanence, adaptability and security into the approach and creating prototypes that can be duplicated and scaled beyond the boundaries of problem solving frameworks.

Makola Market has a rich and colorful history dating back to the 1920s, when it was established as a small trading center by women from the Ga tribe. These women would travel from their rural homes to sell their produce in the market, which was then located near the present-day Accra Central Mosque. Over time, the market grew in size and popularity, attracting vendors and buyers from across the region. In the 1930s, the market was moved to its current location on Kojo Thompson Road, and it continued to expand throughout the 20th century. During the 1960s and 70s, Makola Market played an important role in Ghana’s political and social movements. The market was a gathering place for activists and political leaders, who used it as a platform to promote their causes and rally support.

Today, Makola Market remains one of the largest and most important markets in Ghana, serving as a hub for trade and commerce in the region It sells a wide range of items including fresh produce, textiles, clothing, shoes, jewelry, electronics, household items, and much more. These ranges often also tend to divide the market for ease of access and availability. The hustle and bustle of the market, bargain with vendors for goods and street food all sum up to create a full experience of the place. Throughout our journey in the market, we took a certain route that made us go through these different categories of the economics going on. Every turn and crossing had something new to offer with so much invisible structure to a very openly informal market.

cataloging the market

infrastructure

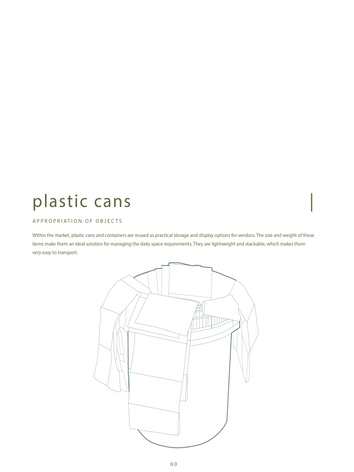

In response to the catalog of spaces and objects we brought forth on being appropriated, the approach we decided to go for was at multiple scales. The table below (on the next page) shows the scale of the intervention and the

infrastructure related to it. For example, in Energy, we have lighting the streets through solar at the neighborhood level, solar panels on the roofs of the buildings at the individual building level and solar powered roof of the

cart for that scale. Similarly we came up with interventions for water, making, storage and shading as well.

the cart

As a part of our intervention, we also decided to scale and build upon one of the tools of infrastructure we were proposing in the Makola market. The idea here was not to redesign a street cart and look into the aesthetics and

design principles of those objects, but to create an apparatus that can be used by everyone in the market to become more self-sufficient. Since we were proposing designs being able to be made out of scraps, we led the initiative

to build a 1:1 street vending cart, with simple mechanisms and frameworks but made entirely out of the scrap materials found in the GSAPP shop. Besides certain hinges, nothing has been purchased and everything was found in the metal workshop. From steel to aluminum to even wood, screws, etc.

the cart manual

As a supplement to the actual cart, weperformed the functions in front of the jury and presented all the drawings and ideas on paper, choreographing every move and element that gets to be revealed at the right time. On the right you also see a ‘build it yourself’ version of the cart with instruction manuals on the steps to take to build our version. The idea was to prove the theory of whether or not you can make a heavy duty street cart entirely out of scrap and given our situation not being in proximity to a scrap yard, I would say the experiment was a success at various levels.